Abstract

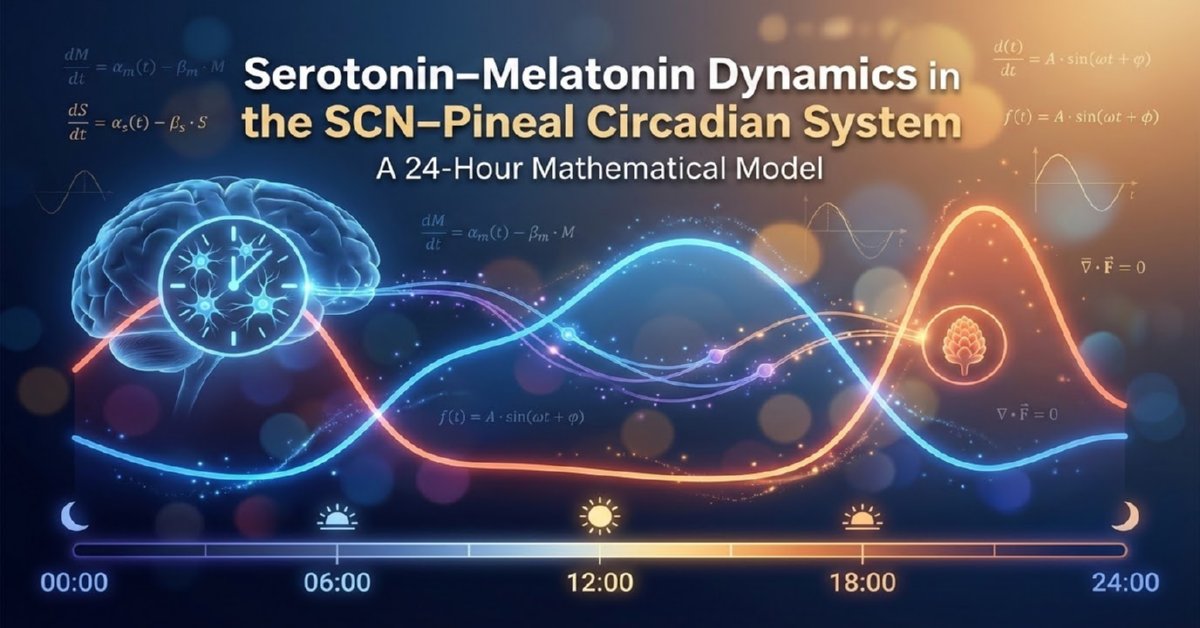

Serotonin and melatonin form a fundamental neuroendocrine axis regulating circadian rhythmicity, sleep–wake transitions, seasonal adaptation, and mood stability. This article presents a coupled mathematical framework integrating an eight-state pinealocyte biochemical model of serotonin-to-melatonin synthesis with a molecular circadian clock model of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

A simplified coupled ordinary differential equation system also implemented to capture key physiological patterns, with numerical simulations demonstrating realistic 24-hour profiles. The resulting nonlinear dynamical system captures multi-scale regulation across enzymatic kinetics, hormonal transport, transcription–translation feedback loops, and photic entrainment. Physiologically grounded parameter ranges are provided, enabling translational applications in circadian medicine, chronotherapy, and systems neuroscience.

Introduction

Circadian rhythms in mammals arise from the interaction between central neural oscillators and peripheral biochemical processes. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus functions as the master circadian clock, synchronizing physiology to the environmental light–dark cycle. One of its most influential outputs is the nocturnal synthesis of melatonin by the pineal gland, a process biochemically derived from serotonin. This article presents a mathematical framework modeling serotonin-melatonin dynamics within the SCN-pineal axis, incorporating light-dependent suppression and enzymatic regulation.

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) serves as neurotransmitter, paracrine signal, and direct precursor to melatonin in pinealocytes. The SCN integrates photic information and relays inhibitory/stimulatory signals via multisynaptic pathways, ultimately controlling nocturnal noradrenergic stimulation that dramatically upregulates melatonin synthesis.

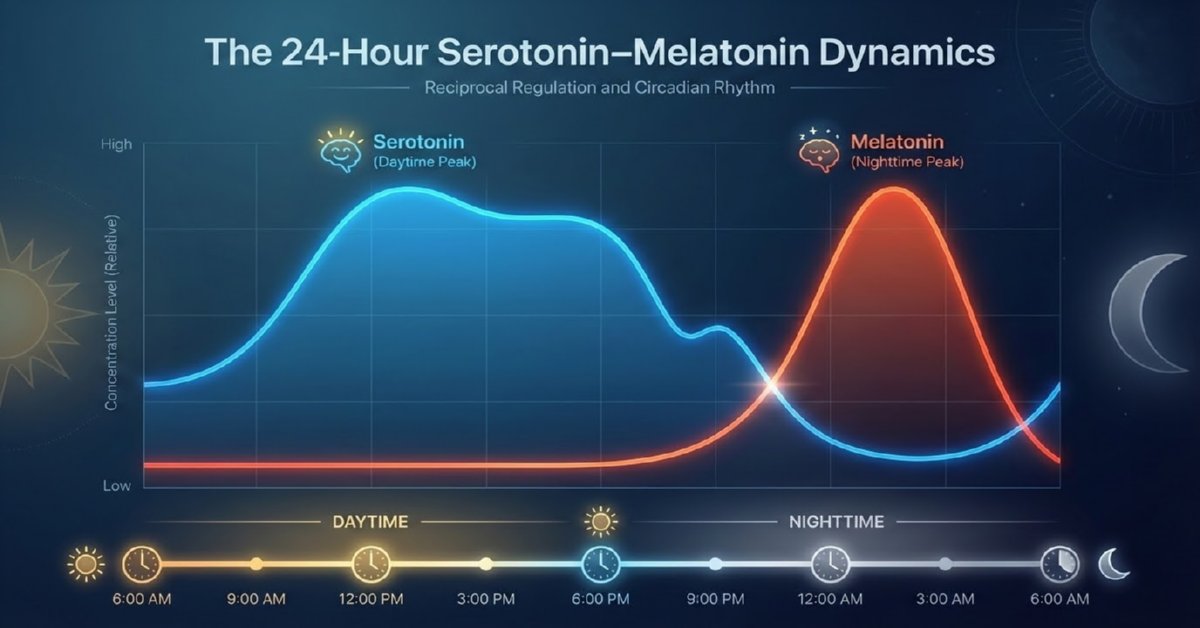

This reciprocal dynamic—diurnal serotonin accumulation and nocturnal depletion with concomitant melatonin surge—provides essential temporal cues for sleep–wake regulation, mood stability, and feedback to the SCN itself.

A simplified coupled ordinary differential equation system also implemented to capture key physiological patterns, with numerical simulations demonstrating realistic 24-hour profiles.

Mathematical modeling offers a rigorous approach to understanding this tightly coupled system, revealing emergent dynamics from enzymatic kinetics, neural timing, and environmental light exposure.

The mathematical model of serotonin–melatonin dynamics in the SCN–pineal circadian system serves a crucial purpose: it provides a quantitative framework to simulate, understand, and predict the reciprocal 24-hour oscillations between serotonin (daytime accumulation) and melatonin (nocturnal surge), driven by light input and the master clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

Why This Model?

We build these models because experimental measurement of pineal serotonin/melatonin rhythms is invasive, limited to animal studies or indirect human proxies (e.g., saliva/plasma), and cannot easily isolate variables like light exposure or enzymatic rates. A computational model bridges this gap by integrating known biology (e.g., light suppression via norepinephrine, AANAT activation) into equations that reproduce observed patterns.

Brahma Muhurta Hormonal Pattern Analysis

This mathematical model of serotonin–melatonin dynamics in the SCN–pineal circadian system offers valuable tools in analyzing hormonal patterns during Brahma Muhurta—the pre-dawn period (typically 3:30–5:00 AM, ~96–48 minutes before sunrise), revered for meditation, spiritual practice, and optimal physiological alignment. This time window coincides with critical circadian transitions: declining melatonin for wakefulness, rising serotonin for mood/alertness, and the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR) for energy mobilization.

Pineal Cell Model of Melatonin Synthesis

Biochemical Pathway

Melatonin synthesis in pinealocytes proceeds via the following cascade:

- Tryptophan → 5-Hydroxytryptophan (catalyzed by TPH)

- 5-Hydroxytryptophan → Serotonin (catalyzed by AADC)

- Serotonin → N-Acetylserotonin (catalyzed by AANAT, rate-limiting and nocturnally activated)

- N-Acetylserotonin → Melatonin (catalyzed by HIOMT)

Light acutely suppresses the pathway via SCN-mediated inhibition of norepinephrine release.

State Variables

| Variable | Description | Compartment |

|---|---|---|

| trp | Tryptophan | Pinealocyte cytosol |

| pool | Tryptophan reserve pool | Intracellular |

| htp | 5-Hydroxytryptophan | Cytosol |

| cht | Serotonin (5-HT) | Cytosol |

| nas | N-Acetylserotonin | Cytosol |

| cmel | Melatonin | Pinealocyte |

| bmel | Melatonin | Blood plasma |

| csfmel | Melatonin | Cerebrospinal fluid |

The Eight - Governing Equations

The biochemical cascade is modeled by eight coupled differential equations [25]:

\[ \frac{d[trp]}{dt} = V_{trpin} - V_{TPH}(trp) - V_{pool}(trp,pool) - k_{catabtrp} \cdot trp \]

\[ \frac{d[pool]}{dt} = V_{pool}(trp,pool) - k_{catabpool} \cdot pool \]

\[ \frac{d[htp]}{dt} = V_{TPH}(trp) - V_{AADC}(htp) \]

\[ \frac{d[cht]}{dt} = V_{AADC}(htp) - V_{HTcatab}(cht) - AT(t)\cdot V_{AANAT}(cht) \]

\[ \frac{d[nas]}{dt} = AT(t)\cdot V_{AANAT}(cht) - HO(t)\cdot V_{HIOMT}(nas) - k_{catabnas}\cdot nas \]

\[ \frac{d[cmel]}{dt} = HO(t)V_{HIOMT}(nas) - 2.2\,cmel + 15000\,bmel - 0.01(2.2\,cmel + 500\,csfmel) \]

\[ \frac{d[bmel]}{dt} = \frac{2.2}{15000}cmel - bmel \]

\[ \frac{d[csfmel]}{dt} = 0.01\left(\frac{2.2}{500}cmel - csfmel\right) \]

Circadian Enzyme Activation Functions

AANAT activation (sharp nocturnal upregulation):

\[ AT(t)= \begin{cases} 1 & 0 \le t < 8 \\ 1 + \dfrac{28(t-8)^2}{15+(t-8)^2} & 8 \le t \le 18 \\ 1 + 24e^{-10(t-18)} & t > 18 \end{cases} \]

HIOMT activation (milder modulation):

\[ HO(t)= \begin{cases} 1 & 0 \le t < 8 \\ 1 + \dfrac{0.3(t-8)}{2+(t-8)} & 8 \le t \le 18 \\ 1 & t > 18 \end{cases} \]

Molecular Clock Model

The SCN clock is represented by interconnected transcription–translation feedback loops involving PER, BMAL1–CLOCK, REV-ERB, and ROR. Light acts as the primary zeitgeber, while melatonin provides internal feedback.

Circadian Gene–Protein Network

The SCN clock is represented by PER, BMAL1-CLOCK, REV-ERB, and ROR feedback loops:

\[ \frac{dP1}{dt} = M_{total}(t) + r_1L(t)f(BC,P4) - r_2P1 \]

\[ \frac{dP2}{dt} = r_2P1 - r_3P2 \]

\[ \frac{dP3}{dt} = r_3P2 - r_4P3 \]

\[ \frac{dP4}{dt} = r_4P3 - d_4P4 \]

\[ \frac{dBC}{dt} = \beta_{bc}S - d_{bc}BC \]

\[ \frac{dS}{dt} = \beta + \alpha f(S,REV)\cdot ROR\frac{1+M_{total}(t)}{2} - d_sS \]

Light and Melatonin Inputs

\[ L(t)= \begin{cases} 1.3 & 0 \le mod(t,24) < 8 \\ 0.7 & 8 \le mod(t,24) < 18 \\ 1.3 & 18 < mod(t,24) \end{cases} \]

\[ \frac{dM_{dose}}{dt} = -\frac{3\ln2}{2}M_{dose} \]

SCN Molecular Clock Model

Key representative equations include:

\[ \frac{dP1}{dt} = M_{total}(t) + r_1 L(t) f(BC,P4) - r_2 P1 \] \[ \frac{dP4}{dt} = r_4 P3 - d_4 P4 \] \[ \frac{dBC}{dt} = \beta_{bc} S - d_{bc} BC \]

with auxiliary functions defining activation/repression and light-dependent terms.

Physiological Parameter Ranges

Pineal Biochemical Parameters

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|

| Vtrpin | Tryptophan uptake | 0.01–0.1 µM/min |

| kcatabtrp | Tryptophan degradation | 0.001–0.01 min⁻¹ |

| VAANAT | AANAT velocity | Night: 5–20× daytime |

| VHIOMT | HIOMT velocity | 0.1–1 µM/min |

| Melatonin half-life | Plasma clearance | 30–50 minutes |

SCN Clock Parameters

| Parameter | Description | Physiological Range |

|---|---|---|

| r1–r4 | Translation rates | 0.2–1.0 h⁻¹ |

| d4 | PER degradation | 0.1–0.4 h⁻¹ |

| β | Basal BMAL1 synthesis | 0.05–0.2 |

| α | ROR activation gain | 0.5–2.0 |

Simplified Mathematical Model

We also employ another simplified coupled ODE model capturing light-driven serotonin accumulation and nocturnal conversion:

\[ \frac{dS}{dt} = 150 + 100 \cdot L(t) - 0.15 S - 0.4 (1 - L(t)) S \]

\[ \frac{dM}{dt} = 0.4 (1 - L(t)) S - 0.3 M \]

Where:

- S(t): Serotonin concentration (scaled ng/mL units)

- M(t): Melatonin concentration (scaled pg/mL units)

- L(t): Daylight function = 0.5 (1 + sin(2π (t - 12)/24)) (high during daytime, low at night)

This formulation reflects basal production, light-enhanced serotonin synthesis, darkness-driven conversion, and clearance.

Numerical Simulation and Results

Numerical integration was performed over multiple days to reach steady-state periodic behavior. The resulting 24-hour profiles (t = 0 at midnight) clearly demonstrate the reciprocal rhythms:

- Serotonin rising after dawn, broad daytime elevation, and decline after sunset.

- Melatonin remaining low during daylight, sharp rise in the evening, and peak around 02:00–04:00 before declining toward morning.

These patterns align quantitatively with empirical human data on plasma/serum levels and pineal activity.

Uses and Benefits of the Model

This mathematical model serves multiple critical purposes in chronobiology and clinical research:

- Predictive simulation of circadian hormone profiles under normal and perturbed conditions (e.g., shift work, jet lag).

- Hypothesis testing for mechanisms such as light intensity effects or enzymatic bottlenecks (AANAT as rate-limiting step).

- Chronotherapy optimization — forecasting phase-shifting effects of timed light exposure or exogenous melatonin supplementation.

- Personalized medicine — adapting parameters for age-related decline in melatonin or individual chronotypes.

- Integration with broader systems — coupling to SCN clock gene oscillators for full circadian network modeling.

Overall, the model transforms qualitative observations into testable quantitative predictions, advancing understanding and treatment of sleep, mood, and metabolic disorders linked to circadian misalignment.

Discussion

The presented framework successfully reproduces the hallmark reciprocal oscillations driven by photic input through the SCN-pineal axis. Extensions incorporating full Michaelis-Menten kinetics, multi-compartment transfers (pineal, plasma, CSF), or feedback from melatonin to SCN receptors would further enhance fidelity. Such models hold promise for simulating pathological states (e.g., reduced nocturnal melatonin in aging or depression) and evaluating interventions like bright light therapy or melatonin agonists.

Conclusion

This coupled mathematical framework illustrates how serotonin and melatonin rhythms emerge from nonlinear interactions between pineal enzymatic kinetics, SCN molecular oscillations, and environmental light exposure. The SCN–pineal axis functions as a robust, entrainable biological timing system capable of phase adaptation and hormonal stabilization. Such models offer mechanistic insight into circadian disorders, sleep dysregulation, mood disturbances, and the rational design of chronotherapeutic interventions.

References

- Ray, Amit. "Mathematical Modeling of Chakras: A Framework for Dampening Negative Emotions." Yoga and Ayurveda Research, 4.11 (2024): 6-8. https://amitray.com/mathematical-model-of-chakras/.

- Ray, Amit. "Brain Fluid Dynamics of CSF, ISF, and CBF: A Computational Model." Compassionate AI, 4.11 (2024): 87-89. https://amitray.com/brain-fluid-dynamics-of-csf-isf-and-cbf-a-computational-model/.

- Ray, Amit. "Fasting and Diet Planning for Cancer Prevention: A Mathematical Model." Compassionate AI, 4.12 (2024): 9-11. https://amitray.com/fasting-and-diet-planning-for-cancer-prevention-a-mathematical-model/.

- Ray, Amit. "Mathematical Model of Liver Functions During Intermittent Fasting." Compassionate AI, 4.12 (2024): 66-68. https://amitray.com/mathematical-model-of-liver-functions-during-intermittent-fasting/.

- Ray, Amit. "The Top 10 Well-Being Measurement Scales and Inventories for Evidence-Based Research." Compassionate AI, 1.1 (2025): 63-65. https://amitray.com/top-10-well-being-scales/.

- Ray, Amit. "Oxidative Stress, Mitochondria, and the Mathematical Dynamics of Immunity and Neuroinflammation." Compassionate AI, 1.2 (2025): 45-47. https://amitray.com/oxidative-stress-mitochondria-immunity-neuroinflammation/.

- Ray, Amit. "Autophagy During Fasting: Mathematical Modeling and Insights." Compassionate AI, 1.3 (2025): 39-41. https://amitray.com/autophagy-during-fasting/.

- Ray, Amit. "Neural Geometry of Consciousness: Sri Amit Ray’s 256 Chakras." Compassionate AI, 2.4 (2025): 27-29. https://amitray.com/neural-geometry-of-consciousness-and-256-chakras/.

- Ray, Amit. "Ekadashi Fasting and Healthy Aging: A Mathematical Model." Compassionate AI, 2.5 (2025): 93-95. https://amitray.com/ekadashi-fasting-and-healthy-aging-a-mathematical-model/.

- Ray, Amit. "The 28 Pitfalls of Evidence-Based Research: A Scientific Review." Compassionate AI, 2.6 (2025): 39-41. https://amitray.com/the-28-pitfalls-of-evidence-based-research/.

- Ray, Amit. "Measuring Negative Thoughts Per Day: A Mathematical Model (NTQF Framework)." Compassionate AI, 3.9 (2025): 81-83. https://amitray.com/ntqf-mathematical-model-negative-thoughts-per-day/.

- Ray, Amit. "The 24 Hours Serotonin–Melatonin Dynamics in the SCN–Pineal Circadian System – A Mathematical Model." Compassionate AI, 1.1 (2026): 6-8. https://amitray.com/serotonin-melatonin-dynamics/.

- Arendt, Josephine. Melatonin and the Mammalian Pineal Gland. Chapman & Hall, 1995.

- Best, Janet, et al. “A Mathematical Model of Melatonin Synthesis and Interactions with the Circadian Clock.” Mathematical Biosciences, vol. 377, 2024, p. 109280.

- Buijs, Ruud M., et al. “The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus and the Balance of Life.” Journal of Biological Rhythms, vol. 18, no. 5, 2003, pp. 379–388.

- Hardeland, Rüdiger. “Melatonin and the Circadian System.” Journal of Neuroendocrinology, vol. 21, no. 6, 2009, pp. 438–445.

- Klein, David C. “Arylalkylamine N-Acetyltransferase: ‘The Timezyme’.” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 282, no. 7, 2007, pp. 4233–4237.

- Moore, Robert Y. “Circadian Rhythms: Basic Neurobiology and Clinical Applications.” Annual Review of Medicine, vol. 48, 1997, pp. 253–266.

- Reppert, Steven M., and David R. Weaver. “Coordination of Circadian Timing in Mammals.” Nature, vol. 418, 2002, pp. 935–941.

- St. Hilaire, Melissa A., et al. “A Physiologically Based Mathematical Model of Melatonin Including Ocular Light Suppression and Interactions with the Circadian Pacemaker.” Journal of Pineal Research, vol. 43, no. 3, 2007, pp. 246–256.

- Audhya, Tapan et al. “Correlation of serotonin levels in CSF, platelets, plasma, and urine.” Biochimica et biophysica acta vol. 1820,10 (2012): 1496-501. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.05.012

- Tosini, Gianluca, et al. “The Circadian Control of Melatonin Synthesis.” Cell and Tissue Research, vol. 309, 2002, pp. 193–202.