7 Limitations of Molecular Docking & Computer Aided Drug Design and Discovery

Over the past decades, molecular docking has become an important element for drug design and discovery. Many novel computational drug design methods were developed to aid researchers in discovering promising drug candidates. In the recent years, with the rapid development of faster architectures of Graphics Processing Unit (GPU)-based clusters and better machine algorithms for high-level computations, much progress has been made in areas such as scoring functions, search methods and ligand-receptor interaction for living cells and other approaches for drug design and discovery.

A large number of successful applications have been reported using a variety of docking techniques. However, despite their success in academic environment for concept validation, their real life application is very limited. There are many obstacles and number of issues remain unsolved. In this article Dr. Amit Ray, explains the key obstacles and challenges of molecular docking methods for developing efficient computer aided drug design and discovery (CADD) methods. Dr. Ray argued incomplete understanding of the underlying molecular processes of the disease it is intended to treat may limit the progress of drug discovery. Here, the seven limitations of present CADD methods are discussed.

In vivo, In vitro and In silico: Experimentation for Drug Discovery

Experimentation for Drug Discovery pathways are classified into three groups: in vivo, in vitro and in silico. In vivo refers to experimentation within the living organism. Animal studies and clinical trials are two forms of in vivo research. In vitro refers to experimentation outside living organisms. Here, studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules in test tubes and flasks. In silico is an expression used to mean “performed on computer or via computer simulation.”

In viov process is difficult and complex. Because it is difficult or impossible to find volunteers to test the performance of a given treatment without endangering them. However, in silico process is easy, as with the advancement of medical imaging, computational power, and numerical algorithms and models, medical and pharmaceutical companies now can reproduce human environments.

Computer-aided drug design and discovery methods

Computer-aided drug design and discovery (CADD) methods are broadly classified into two groups: structure-based methods and ligand-based methods. The most popular and successful methods in drug discovery are structure-based approach. Structure-based approaches are commonly employed to screen large small-molecule datasets, such as online data-banks or smaller sets such as tailored combinatorial chemistry libraries. The structure based drug design works when we know the structure of the target and the ligand based drug design is used when we do not know the structure of the target, their ligand and their potency. Ligand-based CADD exploits the knowledge of known active and inactive molecules through chemical similarity searches or construction of predictive, quantitative structure-activity relation (QSAR) models. With structure based approach, one tries to calculate binding affinity score between a target and a candidate molecule based on a 3D structure of their complex.

Molecular Docking

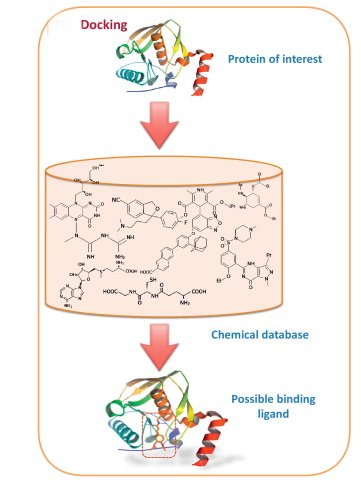

Docking is an automated computer algorithm that determines how a compound will bind in the active site of a protein. Protein–ligand docking algorithm is most popular. It consists of two main steps: conformation generation and scoring.

Docking is an automated computer algorithm that determines how a compound will bind in the active site of a protein. Protein–ligand docking algorithm is most popular. It consists of two main steps: conformation generation and scoring.

The conformation generation techniques uses sampling techniques to generate different ligand orientations at different positions inside the protein binding pocket. Each of these conformations are evaluated by a scoring function. The highest scoring ligand conformations are ranked in a list as a result. In flexible ligand docking, the size of the conformational space or the search space depends on the volume of the protein binding pocket and the number of rotatable bonds of the ligand of interest. In the energy landscape of the search space is determined by the energetic properties of protein–ligand binding which is more complex and rugged in shape.

To be able to search quickly and intelligently over the huge conformational space, heuristic or meta-heuristic algorithms are used. Often they settled on near-optimal solutions instead of the global optimum solutions. Current researches are mostly focused on finding the global optimum solutions. Finding the global minimum or the complete set of low energy minima on the free energy surface when two molecules come in contact is commonly referred as the “docking problem”.

Search Algorithms for Drug Design

Every docking process can be described as a combination of a search algorithm and a scoring function. The search algorithm generates a large number of poses of a small molecule in the binding site. The docking methods extensively employ search algorithms based on Monte Carlo, genetic algorithm, fragment-based and molecular dynamics. The commonly used stochastic or random approaches are: Monte Carlo, simulated annealing, evolutionary algorithms, and Swarm Optimization.

A piggyback or drug re-positioning approach to drug discovery

Two alternative drug discovery strategies: de novo drug discovery and piggy-back strategies.

The ‘piggyback’ approach, utilizes identified active compounds that have already been thoroughly evaluated as drugs or leads, as starting points in drug development. The label extension strategies on the other hand, involves extending indications of an existing treatment to another disease.

Drug repurposing (also known as drug repositioning) aims at identifying new uses for already existing drugs. A popular strategy for academic groups has been to “re-purpose” or reuse existing chemical matter, target knowledge, and other data from human or animal drug discovery campaigns in order to cut down on the time and cost of advancing a program from hit to lead to clinical candidate.

The many terms for repurposing strategies can be grouped into four major categories, which are a) drug repurposing, b) target repurposing, c) target class repurposing, and d) lead repurposing. Here, approved chemical matters are profiled in terms of safety and pharmacokinetics, giving an indication of tolerated human doses and any likely side effects. As a result, both the time and cost of drug development are drastically reduced using this approach. Target repurposing offers several benefits over other strategies. The chemical matter that targets the host protein is often an approved drug or clinical candidate, which is then used as a starting point to develop compounds that inhibit the parasitic target.

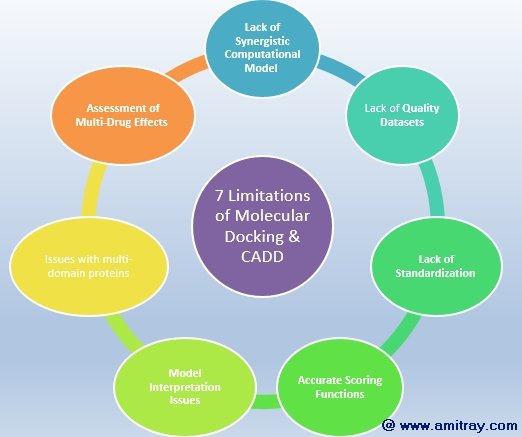

Seven Limitations of Computer Aided Drug Design and Discovery

The seven main obstacles of Molecular Docking & computer aided drug discovery are as follows: Lack of Synergistic Computational Model, Lack of Quality Datasets, Lack of Standardization, Lack of Accurate Scoring Functions, Overcoming the Model Interpretation Issues, Issues with multi-domain proteins, and Assessment of Multi-Drug Effects.

One of the biggest challenges in CADD is target flexibility. Most molecular docking tools provide high flexibility to the ligand, while the protein is kept more or less fixed or provided with limited flexibility to the residues present within or near the active site. There are various attempts to provide complete molecular flexibility to the protein. However, this increases the space and time complexity of the computation exponentially. Designing a single, rigid structure inhibitors or drug molecules may also lead to an incorrect result.

1. Lack of Synergistic Computational Model

Synergy is the combined power of a group of things when they are working together that is greater than the total power achieved by each working desperately. Synergy manifests itself quantitatively or qualitatively: synergistic effects can be smaller or larger or they can be entirely different from what was expected. There is no single mathematical model that can be used uniformly to detect and quantify synergy. Traditionally, two independent parameters: the target similarity score (TSS) and the protein interaction score (PIS) are used for quantitatively measure the degree functional association between the target and ligand.

Better strategies are necessary toward better understanding of drug synergy, including the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network-based methods, pathway dynamic simulations, synergy network motif recognitions, integrative drug feature calculations, and “omic”-supported analyses. Synergistic computational models are required to study proteins functions in development, metabolism and signaling, pharmacology/toxicology, molecular genetics and development, biochemistry, ecology and metabolic engineering. Synergy can be found in the interaction between communities of organisms.

2. Lack of Quality Database:

Drug discovery not only needs the reliable models, but also reliable data. The ModBase, PMP, and SWISS-MODEL are the three common databases are often used for drug discovery. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) (2013), established in 1971 at the Brookhaven National Laboratory, and the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, are among the most commonly used data bases for protein structure. PDB currently houses more than 81,000 protein structures. The Swiss-Model server is one of the most widely used web-based tools for homology modeling. The SWISS-MODEL contained 3.2 million entries for 2.2 million unique sequences in UNIPROT data base.

These databases are good for concept validation, prototype development and small academic research and experiments but they are far away from the requirements of exhaustive drug analysis and discovery in real life situations.

One of the main limiting factor is the validity and accuracy of methods implemented for the prediction of drug–protein or drug–disease signatures. However, while docking strategies have undoubtedly become more sophisticated, they still suffer from high false-positive rates, which beg the question of whether our understanding of ligand–protein binding is comprehensive enough and if the focus on ligand–protein signatures is sufficient for accurate pharmacodynamics and clinical outcomes.

The quality of the data determines the quality of the final model. The data used for modeling should be obtained under the same laboratory conditions and using the same experimental protocols. At the dawn of computer history, Charles Babbage, the creator of the first programmable computer was asked: “Pray, Mr. Babbage, if you put into the machine wrong figures, will the right answers come out?”. The answer is still the same: starting from wrong data will inevitably compromise the results, regardless of the accuracy of the calculation performed. Therefore, the very first rule of any scientific simulation should be to ensure the highest possible quality of input data, which, specifically for docking, refers to ligand and target input structures.

Molecular structures form a basis for calculation of descriptors. Nowadays a variety of computer software packages are available to calculate descriptors and hundreds of them can be easily calculated. A selection of the most relevant descriptors represents a basic problem in the developing QSAR models.

3. Lack of Standardization for Testing and Validating the Results

Today, a basic concept is accepted that a model should be tested with an independent test set. An independent test dataset means a set that was never used in the model developing procedure. Before the start of the modeling development a test set is excluded from the compiled data set. Again, different strategies are possible. Usually, a random selection is performed, or, alternatively, the objects for the test set are selected equivocally from the entire model's domain.

Lack of standardization, particularly regarding data interchangeability and manipulation and reproducibility of results. One major stumbling block to the advancement of protein–ligand docking validation has been the lack of a standard test set agreed upon and used by the entire community. The researchers often significantly process and manipulate the data before using them as input for docking programs. There is a need for standardized docking workflow which can divide the docking into a series of protocols.

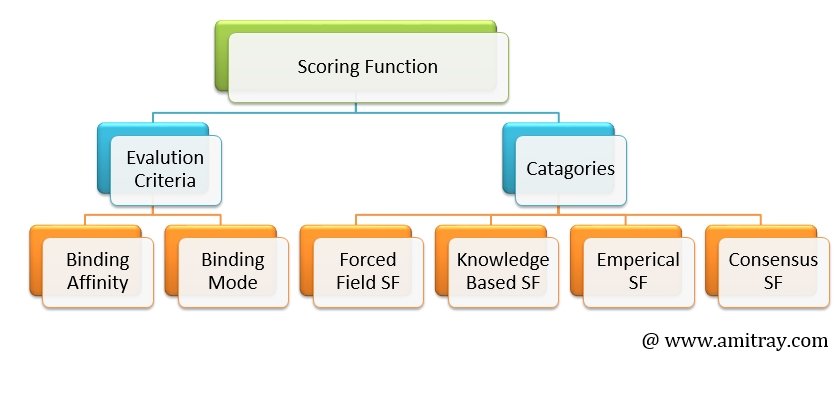

4. Lack of Accurate Scoring Function

Scoring functions are mathematical functions used to approximately predict the binding affinity between two molecules after they have been docked. In this process, a large number of binding poses are evaluated and ranked using a scoring function. The scoring function is a mathematical predictive model that produces a score that represents the binding free energy, and hence the stability, of the resulting complex molecule. It calculates the score or binding affinity of a particular pose, which represents the thermodynamics of interaction of the protein–ligand system, in order to distinguish the true binding modes from all the others explored, and to rank them accordingly. Scoring functions (SFs) are typically employed to predict the binding conformation, binding affinity, and binary activity level of ligands against a critical protein target in a disease’s pathway. NNScore , RFscore, and SFCscore are commonly used scoring functions.

Most of the today’s scoring functions are generic models derived from the large-scale experimental data of ligand–target complexes and are presumably applicable to all sorts of target classes. However, previous comparative studies have revealed that a universally accurate scoring function is still out of reach.

5. Challenges with Model Interpretation

Identification of the target protein and the active site with an ideal ligand is not sufficient to reach any logical end in a drug discovery process. There are many obstructions, which come in the way of designing a new drug compound to a final drug molecule.

The protein fluctuates through this ensemble depending on the relative free energies of each of these states, spending more time in conformations of lower free energy. Ligands are thought to interact with some conformations but not others, thus stabilizing conformational populations in the ensemble. Therefore, docking compounds into a static protein structure can be misleading, as the chosen conformation may not be representative of the conformation capable of binding the ligand.

Currently, much effort is directed towards machine learning, which is most helpful in elucidating non-linear and non-trivial correlations in data. NNScore , RFscore, and SFCscore are among the most distinguished examples. However there are only a few freely accessible scoring functions and even fewer that are fully open source. Machine learning scoring functions consist of four main building blocks: descriptors, model, training set and test set.

The sensitivity of docking programs to the initial ligand conformation is still an open question. The number of ligand conformations that need to be explored during the docking process to qualify as ‘exhaustive’ has not been established.

6. Issues with Multi-domain Proteins

Proteins are frequently composed of multiple domains. Determining the structure of multi-domain complexes at atomic resolution is critical to understanding the underpinnings of much of biology. However, important challenges still remain in multi-domain docking prediction. For example, in cases with significant mobility, such as multi-domain proteins, fully unrestricted rigid-body docking approaches are clearly insufficient so they need to be combined with restraints derived from domain-domain linker residues, evolutionary information, or binding site predictions.

7. Lack of Procedures for Multi-Drug Effect Assessment

The rise of multi-drug resistant and extensively drug resistant bacteria around the world, poses a great threat to human health and defines a need to develop new, effective and inexpensive anti-bacteria agents. The mystery of chemicals and of chemistry is how structure or substructures are related with chemical behavior and activity. Any change in chemical structure results in different chemical behavior. It is of great interest to predict how the presence of a ligand changes the chemical structure and behavior of other chemicals . If we could do so, then more effective drugs can be developed as well as the development of more effective, but safer chemicals for societal use.

Conclusion:

Computer aided drug discovery is vital for the drug discovery part of the funnel. However, presently, the academic computational models are deeply limited by crude datasets or incomplete understanding of the underlying molecular processes of the disease it is intended to treat. True deeper intelligence about the diseases and their interactions are lacking in the present day models. One way to address these limitations is to integrate ligand, target, phenotype and biological network based approaches, with deeper reinforcement learning techniques, which could likely multiply the predictive power. Further development of more sophisticated techniques that can address the shortcomings of existing computational approaches will be required to efficiently turn shelved compounds into new medicines and predict new indications for existing drugs.

References:

- Ray, Amit. "Artificial Intelligence in Precision Medicine." Compassionate AI, 2.5 (2018): 57-59. https://amitray.com/artificial-intelligence-precision-medicine/.

- Ray, Amit. "Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain for Precision Medicine." Compassionate AI, 2.5 (2018): 60-62. https://amitray.com/artificial-intelligence-and-blockchain-for-precision-medicine/.

- Ray, Amit. "7 Limitations of Molecular Docking & Computer Aided Drug Design and Discovery." Compassionate AI, 4.10 (2018): 63-65. https://amitray.com/7-limitations-of-molecular-docking-computer-aided-drug-design-and-discovery/.

- Ray, Amit. "AI-Driven PK/PD Modeling: Generative AI, LLMs, and LangChain for Precision Medicine." Compassionate AI, 1.3 (2025): 48-50. https://amitray.com/ai-driven-pk-pd-modeling-generative-ai-llms-and-langchain-for-precision-medicine/.

- Ray, Amit. "Mathematical Model of Healthy Aging: Diet, Lifestyle, and Sleep." Compassionate AI, 2.5 (2025): 57-59. https://amitray.com/healthy-aging-diet-lifestyle-and-sleep/.

A Computational Approach for Identifying Synergistic Drug Combinations

Performance of machine-learning scoring functions in structure-based virtual screening

Same but not alike: Structure, flexibility and energetics of domains in multi-domain proteins are influenced by the presence of other domains

Computer-Aided Drug Design Methods

Read more ..

Docking is an automated computer algorithm that determines how a compound will bind in the active site of a protein. Protein–ligand docking algorithm is most popular. It consists of two main steps: conformation generation and scoring.

Docking is an automated computer algorithm that determines how a compound will bind in the active site of a protein. Protein–ligand docking algorithm is most popular. It consists of two main steps: conformation generation and scoring.